The following text was originally published in Spanish on May 28, 2020 by the Fundación por la Arquitectura of the Architects and Landscape Architects Association of Puerto Rico (CAAPPR) as part of their campaign ”Arqui Desde Casa” during the lockdown period due to Covid-19. Scroll down for English translation.

La piel de la arquitectura de Henry Klumb

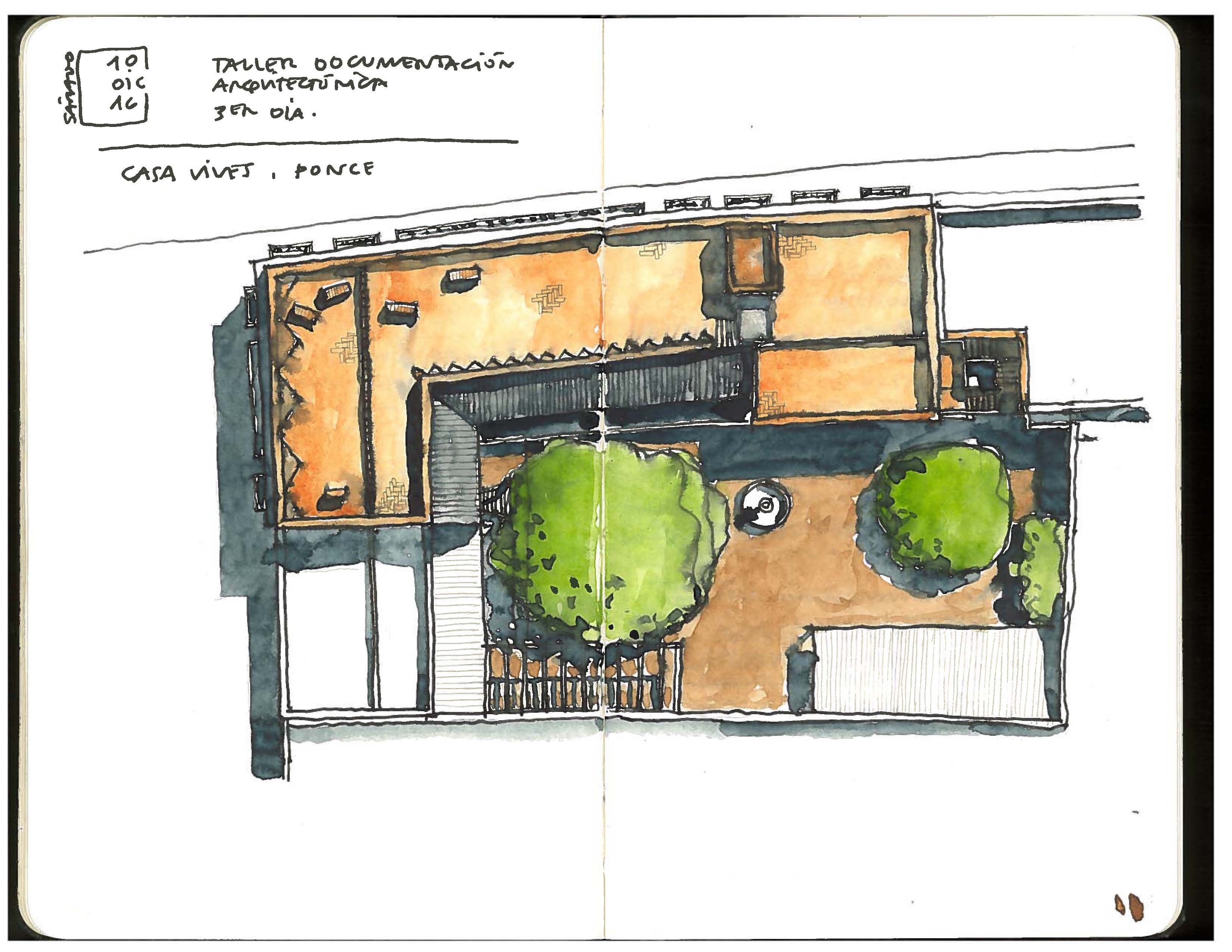

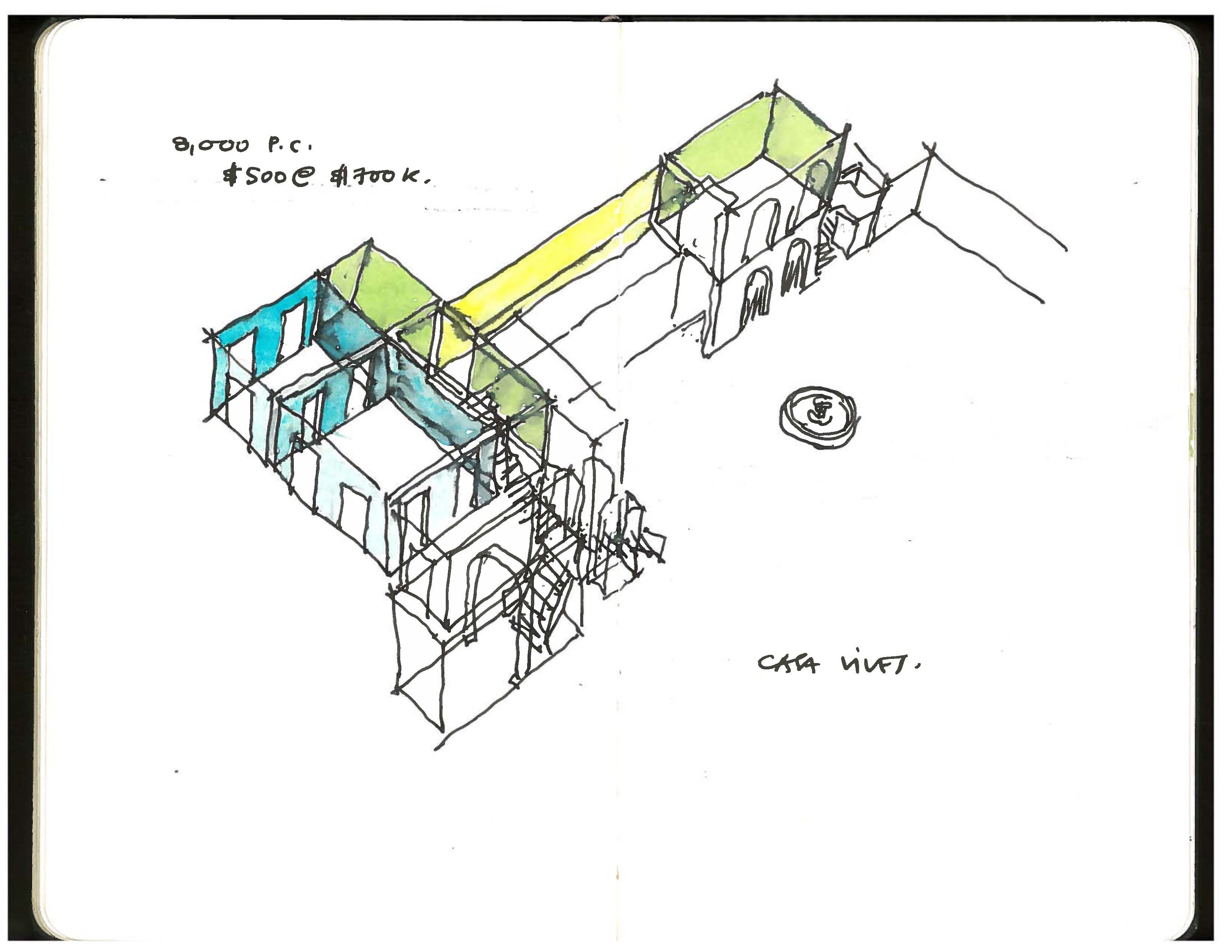

Las siguientes acuarelas se centran en la obra del arquitecto alemán radicado en Puerto Rico, Henry Klumb, especialmente en los quiebrasoles y mamparas que utilizó en la mayoría de sus obras institucionales.

Mucho se ha escrito sobre el trabajo de Klumb y su deseo — casi un predicamento — de producir una arquitectura adaptada al trópico, emplazada para beneficiarse de la ventilación cruzada, garantizando su habitabilidad sin exponerla al innecesario consumo energético.

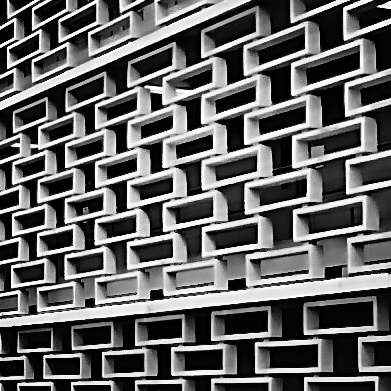

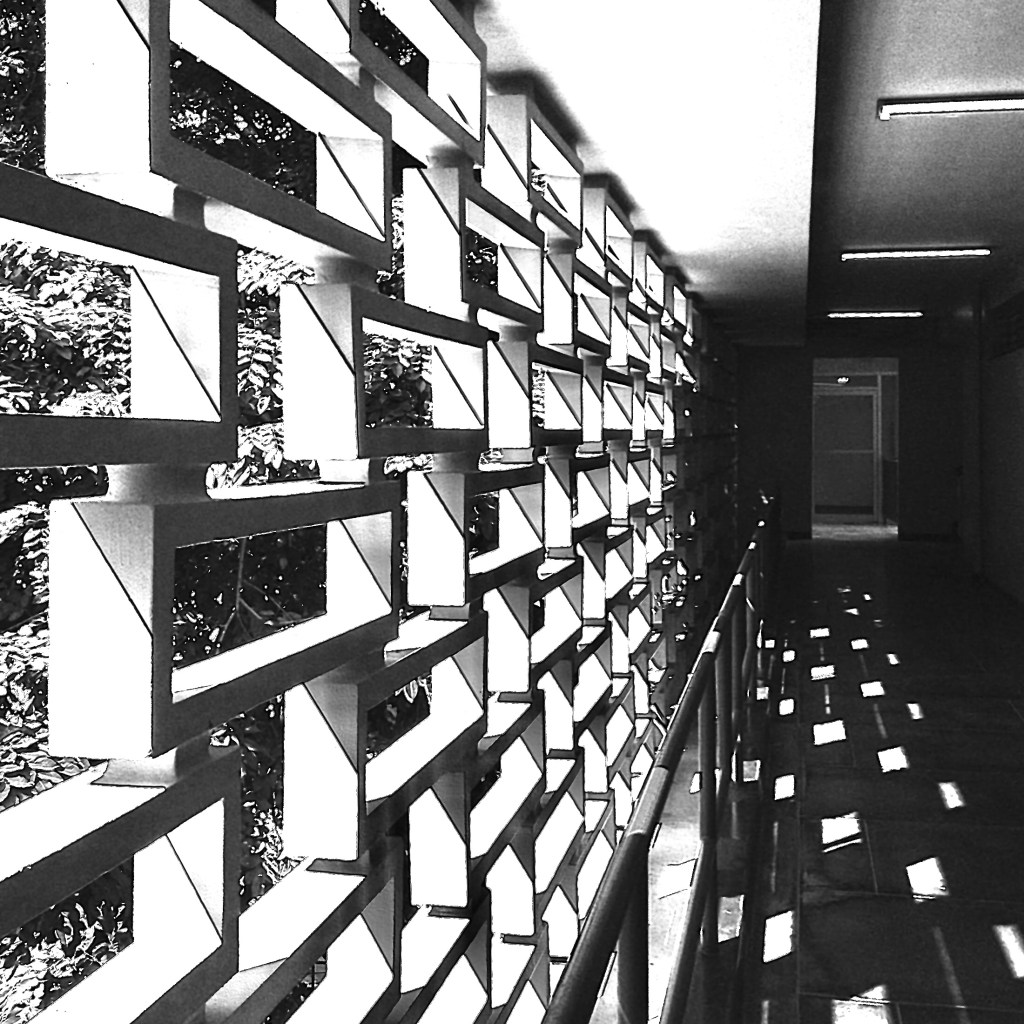

Aquellos que han experimentado su obra en persona reconocen el rol protagónico de los sistemas de quiebrasoles o brise-soleils en la experiencia de su arquitectura. En especial la forma en que estos matizan el impacto del sol, contribuyen a la privacidad (y, en muchos casos, seguridad) y la capacidad de relacionar la actividad del exterior con la de los espacios interiores.

Ahora bien, a quien haya mirado de cerca los edificios que incorporan estas pieles permeables, poca imaginación hace falta para reconocer que mucho del carácter de estas estructuras recae en estos elementos prefabricados.

Invito a idearnos estos edificios sin su piel, cuando entonces se revela una arquitectura de pocas complicaciones o pretensiones, con ventanas de celosías de madera, aluminio (tipo “Miami”) o de paños de cristal, junto a muros lisos de bloques de cemento empañetados, en fin, una arquitectura opuesta a lo que muchos esperan de obras institucionales.

Tal señalamiento no propone restarle mérito a la obra de Klumb, pues excepciones sobresalientes abundan en su arquitectura. Solo basta mencionar el patio de la Escuela de Derecho, el corte transversal de administración de empresas y la capilla del convento dominico, por mencionar solo unos cuantos.

Por el contrario, el argumento recae más que nada en los volúmenes que se visten de los quiebrasoles, donde se reconoce en el diseñador la habilidad de producir una arquitectura “corriente” o más bien “plain” y dotarla de aspiración estética mediante el sencillo acto de enriquecer sus fachadas, despejadas de elementos prescindibles a través de su piel.

Edificios Osuna, O’Neill, Betances y Rivera de Alvarado

(Facultades de Administración de Empresas y Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras)

Edificio IBM

(Kings Court y Calle Loiza, San Juan)

Escuela de Derecho

(Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras)

Convento de los Frailes Dominicos

(Bayamón, Puerto Rico)

Biblioteca José M. Lázaro

(Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras)

The skin of Henry Klumb’s architecture

The following watercolors focus on the work of the German architect based in Puerto Rico, Henry Klumb, especially on the sunscreens that he employed in most of his institutional works.

Much has been written about Klumb’s work and his desire – almost a predicament – to produce an architecture adapted to the tropics, located to benefit from cross-ventilation, guaranteeing its habitability without exposing it to unnecessary energy consumption.

Those who have encountered his work in person recognize the protagonist role the sunscreen or brise-soleil systems play in the architectural experience. Especially the way in which these diminish the sun’s impact, contribute to privacy (and, in many cases, security), and their capacity to merge the interior spaces with their surrounding environment.

Whoever has glanced closely at the buildings that incorporate these permeable sinks, little imagination requires to recognize that much of the character of the structures lies in the precast elements.

I invite to visualize these buildings without their skin, only then an architecture of few pretentions is revealed, one of cement plastered CMU walls with aluminum, wood, or, glass pane windows. In short, an architecture contrary to what many would expect of institutional buildings.

Such assertion does not intend to detract from Klumb’s work, since outstanding exceptions abound in his architecture. For example, the courtyard of the Escuela de Derecho, the cross-section of the business administration building, and the chapel of the Dominican convent, to name just a few.

On the contrary, more than anything, the argument is aimed at the volumes that are dressed with these sunscreens, where the designer is recognized for his ability to produce “ordinary” or rather “plain” architecture and endow it with aesthetic aspiration through the simple act to enriching its façades, cleared of expendable elements through their skin.

All photos by author unless specified otherwise.

Street view downloaded 05.31.2020 from https://www.top10puertorico.com/bs-entertainment/loiza-street/ Edited to b&w and cropped for subject emphasis.

Colección de fotos del periódico El Mundo

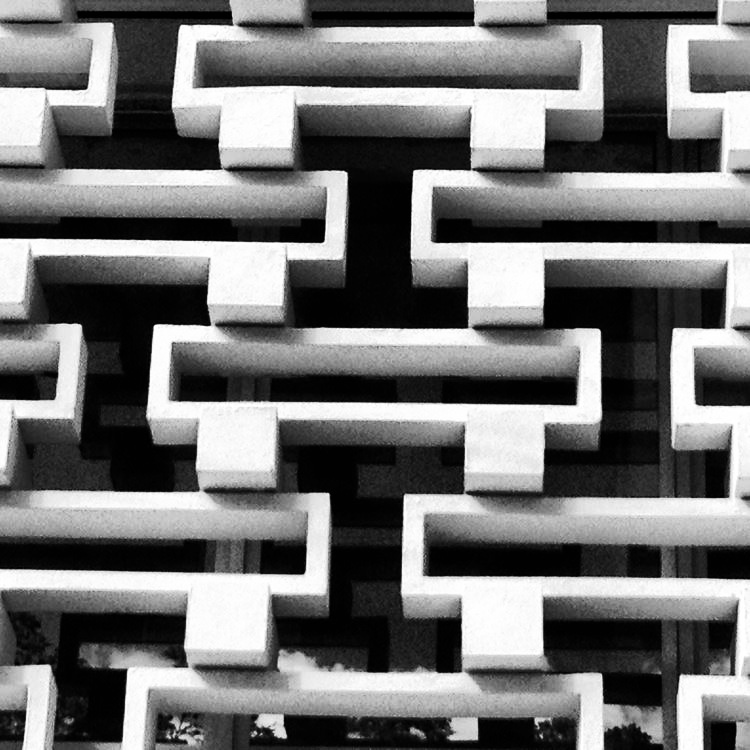

The brise-soleil system consists of a series of rectangular prefabricated elements of approximately 1ft height, 4ft long, 10in deep, and 2 1/2in thick installed in a staggered pattern. Each block seats on concrete trapezoidal prisms that embed to each element to keep the skin in place and restrain its lateral movement.

Rectangular elements of approximately 1ft height, 4ft long, 10in deep and 2 1/2in thick (same as described above). The system is also installed in a staggered pattern but in this case, the separators are a series of solid concrete blocks, 6in x 6in x 12in. Each element is embedded with concrete pegs to restrain the system from lateral displacement.

The most complex skin system developed by Klumb. Consist of a series of prefabricated reinforced concrete columns and slabs.

The columns are shaped in zig-zag or serpenting pattern to provide a seat for the slabs. The columns are shaped in a way they coupled with the slabs (male and female) restraint the displacement of the tablets.

The columns are installed at equal spacing (about 18in apart) and each pair is mirrored to provide a staggered pattern for the slabs. The slabs are 2 1/2” thick x 18in wide and 24in deep, while the columns have a thickness of 3in.

Main Sanctuary (view from baptistry)

Main Sanctuary (view from baptistry) Main Sanctuary (towards the altar)

Main Sanctuary (towards the altar) Main Sanctuary (view from the altar)

Main Sanctuary (view from the altar) Choir (looking towards the Main Sanctuary)

Choir (looking towards the Main Sanctuary)