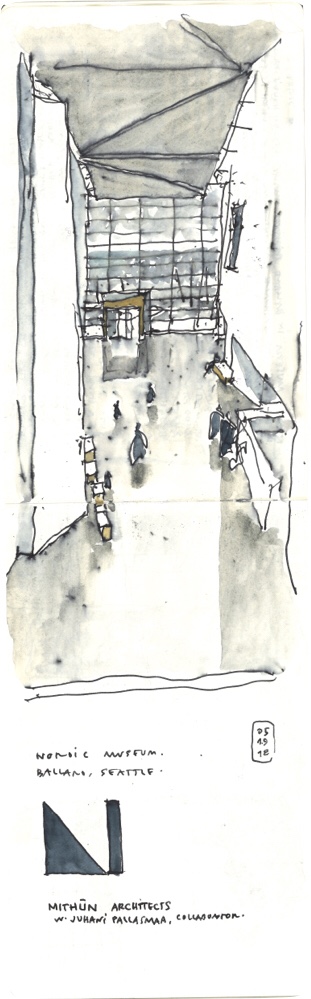

The Nordic Museum in Ballard is a welcome addition to Seattle.* Designed by MITHŪN Architects in collaboration with Finnish architect and historian Juhani Pallasmaa, the institution exhibits Nordic art and cultural traditions.

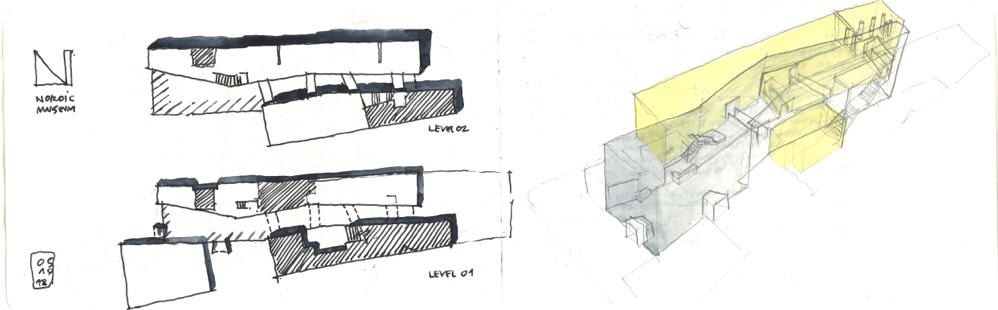

At first glance, it is difficult not to point out the building’s resemblance to Steven Holl’s Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki, Finland. Juhani Pallasmaa, who collaborated on both designs, could account for these similarities. Both museums share a spatial organization in which two longitudinal volumes flank a multistory atrium of comparable geometry and proportions.** Yet the apparent formal kinship conceals two fundamentally different attitudes toward the atrium—not as image, but as spatial organizer. Despite its smaller scale and more modest budget, the Nordic Museum’s atrium succeeds precisely where the Kiasma’s falls short: in serving as a functional organizing element rather than merely a monumental gesture.

Despite their initial similarities, differences abound. Upon close inspection, at the Nordic—probably due to its reduced scale—MITHŪN managed to activate the atrium space much more gracefully than at the Kiasma.

While both museums offer similar programmatic experiences at ground level—where the cafe, reception desk, and museum store animate and promote social interaction upon entry—at the Nordic, these activities appear more seamlessly integrated with the main space simply because they remain visually and spatially open to the atrium.

At Helsinki, by contrast, the atrium—in great part due to its size (50ft tall by about 200ft long)—remains somewhat segregated from the ancillary programs, even if directly adjacent to them. Beyond its scale, the separation is emphasized by the atrium being enclosed by tall, exposed-concrete walls with minimal openings in relation to their height.

More critically, the atrium at the Kiasma serves primarily as a monumental vestibule, while at the Nordic, the atrium doubles as the spine that organizes the museum.*** The multi-story hall is crucial as it helps visitors understand the museum’s layout without revealing inside exhibits. Additionally, a centrally located fireplace offers Seattleites a sense of place without an admission fee.

Mithūn based their design for the atrium on the geological formations known as fjords. These remarkable canyon-like landforms visually separate landscapes that nevertheless constitute a unified ecosystem throughout the Nordic Regions (including the Pacific Northwest)—were created millions of years ago by the movement of glaciers. The metaphor seems appropriate since the atrium becomes the spine that organizes the museum not symbolically, but operationally.

Such is not the case with its European sibling, where its atrium contorts—somewhat like a funnel—and the monumental scale consequently offers few cues on how to progress. An overhanging concrete ramp presents itself—almost as the visitor’s only viable option—to initiate our tour; however, one must find the ticketing booth first to gain access. That said—once started—the spatial sequence at Kiasma is well-executed. As is customary in great museums, it allows the visitors to traverse through without retracing their steps.

A more straightforward—yet successful—spatial sequence is experienced at the Nordic, not without some minor inconveniences. As illustrated above, the longitudinal atrium suggests the spatial arrangement. A series of bridges connecting the upper galleries, weaving across the atrium, are visible. Mid-way through the Fjord, a gallery opens up, and a monumental stair invites you to ascend.

Once on the second level, the sequence is free, and the bridges assist the visitor to zig-zag from one side to the next without having to go back on the already traveled path. One of the “parallel” bars extends beyond the other. The longest one houses a small library space and administrative offices. But before reaching the library, a flight of stairs invites us to descend, culminating the spatial sequence right behind the reception desk where the tour started, but conveniently inside the museum store.

Yet this otherwise legible spatial sequence has one notable exception: the East Garden. Unlike the carefully choreographed interior route, the garden functions as a spatial cul-de-sac. Visitors who bypass the second level and head toward the garden find the museum’s organizing logic abruptly dissolving—no onward path, no alternative route, only the need to retrace their steps. This seems less an intentional pause than a residual space shaped by operational or administrative constraints, momentarily undermining the atrium’s otherwise successful role as the museum’s spine.

Ultimately, the Nordic Museum demonstrates that architectural success isn’t simply a matter of budget or prestige. Despite its more modest scale and less refined material palette, Mithūn’s design achieves something Holl’s larger, more expensive Kiasma struggles with: an atrium that genuinely organizes and activates the museum experience. The fjord metaphor works precisely because it’s functional, not merely conceptual. Yet one can’t help but wonder what the Nordic might have been with Helsinki’s construction budget—or conversely, whether the Kiasma’s monumental ambitions might have benefited from Seattle’s more pragmatic, integrated approach to the central space. The comparison reveals that in museum design, spatial clarity and programmatic integration often matter more than material luxury.

ENDNOTES:

*After living in Seattle for over eight years, one could argue that besides OMA’s Public Library Downtown or Steven Holl’s jewel box Chapel of Saint Ignatius in First Hill, there are few noteworthy contemporary cultural buildings. The dominance of design-build delivery methods and commercial construction pressures seem to constrain the kind of ambitious institutional architecture seen in other cities or federal projects—limiting the refinement of interior spatial sequences and material detailing that distinguish truly exceptional cultural buildings.

Don’t get me wrong; there are numerous notable additions and interventions to institutional buildings throughout the city. For example, the Space Needle renovation by Olson Kundig, or even LMN’s restoration and expansion to the SAM Asian Art Museum, are among the best.

There are also great contemporary public spaces, like the recent James Corner Field Operations’ Waterfront Park transformation—reconnecting the city to Elliott Bay—or the earlier Weiss/Manfredi Olympic Sculpture Park and Berger Partnership’s Magnuson Park.

**After careful examination of both projects, it becomes evident that the scale of both museums varies considerably, as do their construction finishes. Their formal complexities also differ considerably. At the Kiasma, the signature of its lead designer Steven Holl creates an unparalleled display of double qheight spaces, spiraling stairs, sculptural ramps, and beautifully crafted rooms, all bathed by sunlight piercing through skylights and full-sized glass walls and ceilings of different types.

For information on the Kiasma visit: https://www.archdaily.com/784993/ad-classics-kiasma-museum-of-contemporary-art-steven-holl-architects

***Since my last visit to Helsinki in 2003, the Kiasma Museum has undergone a series of renovations. Most notably in 2016 the museum completed an interior refurbishment of the entrance level, including the lobby and museum shop, aimed at improving functional clarity and creating a more welcoming, lounge-like atmosphere. These interventions focused primarily on operational clarity rather than on rethinking the atrium’s spatial agency or its capacity to guide visitors intuitively.

Subsequent renovations between 2020 and 2022 addressed significant envelope and roof performance issues and upgraded building systems, but did not substantially modify the atrium’s role as a monumental vestibule. As such, the observations presented here regarding the atrium’s spatial behavior and its relationship to visitor movement remain largely applicable.

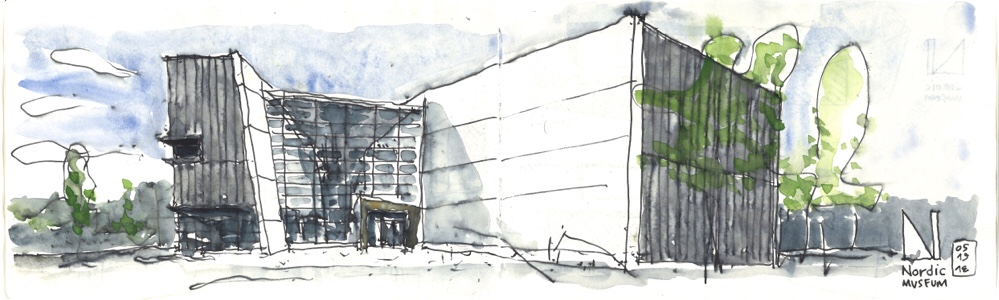

SITE

Understanding the Nordic Museum’s site helps explain why the atrium functions so effectively as an organizing spine. The Museum sits on a two-acre lot along NW Market Street, a short distance from the shoreline of Salmon Bay and a few feet away from the Hiram Chittenden Locks, better known as Ballard Locks. The site is longitudinal (slightly trapezoidal), and it is about the same area as a typical residential block in the neighborhood. This narrow, elongated site naturally suggested the two parallel bars flanking a central atrium—the very configuration that MITHŪN exploited to create a legible circulation sequence.

Along Market Street, the building adheres to the street frontage, receding at the corner of 28th Avenue, where a small plaza signals the entrance. Three additional entries give access to the building; two secondary entries along Market Street (through the museum store and cafe) and another on the south side of the building, allowing access to visitors from the parking lot. The multiple entry points reinforce the atrium’s role as the central reference point from which all circulation is organized.

However, the average visitor coming from downtown Seattle traverses the entire length (400 feet) of the museum along Market Street. Many regard this approach as an unfortunate urban response since the main façade, along Market Street is for the most part, impenetrable. For others, the blank façade, clad in metal panels, is reminiscent of the warehouses that occupied the site and others existing along the shore. This extended approach, however, heightens the drama of entering the atrium—the moment when the building’s organizational logic suddenly becomes clear.

ADDITIONAL COMPARISONS

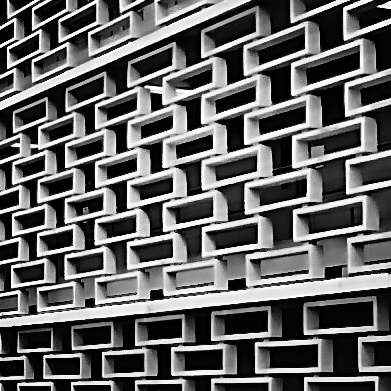

Besides the similarities, there seems to be a chasm between the two structures. The construction materials employed at the Kiasma are of far superior quality and were assembled with the utmost attention to detail. At the Nordic, by contrast, soaring construction costs in Seattle appear to have taken a heavy toll on the selection of materials and finishes.

For example, the interior walls at the central atrium of the Kiasma are made of exposed white concrete. At the Nordic, gypsum board was used instead. Also, the exterior cladding at the Nordic is made of pre-finished standing-seam and fiber cement board. At the Kiasma, by contrast, hand-sanded aluminum panels, ‘u-glass’ curtain walls, acid-reddened brass mullions, and zinc (with titanium and copper alloy to allow a patina with time) standing-seam panels with titanium and copper alloy finish were employed. These are just a few material comparisons, but many abound.

At first, the comparison seems unfair—surely the Kiasma, with its larger footprint of around 130,000 square feet compared to the Nordic’s 57,000 square feet, had a proportionally larger budget. However, a closer look at their construction budgets reveals a surprising reality that helps explain the material disparity.

The construction budget for the Kiasma Museum in 1998 was $38M (about $58.5M in 2017). By contrast, the Nordic’s budget was $47M. Despite having less money overall, the Kiasma’s cost per square foot was around $450 (in today’s money) while the Nordic’s was $850 per square foot. In other words, the Nordic Museum cost nearly twice as much per square foot to build, yet displays noticeably inferior materials. This paradox illustrates Seattle’s inflated construction costs: MITHŪN had to spend far more money to achieve far less material refinement.

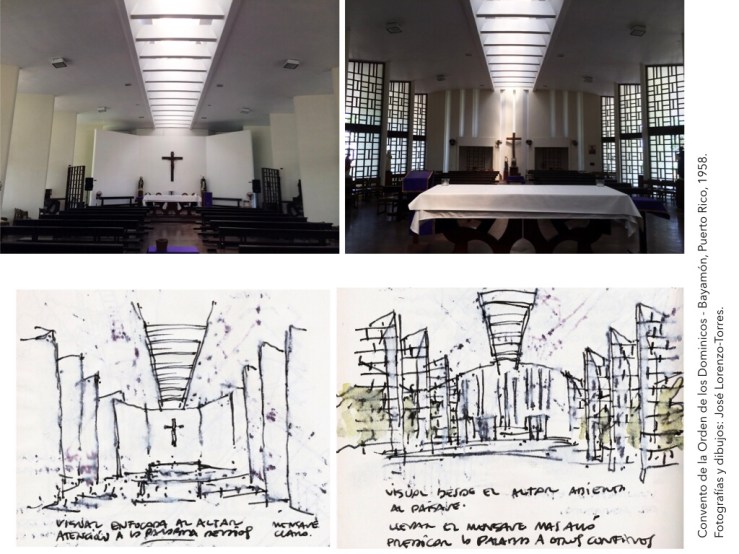

The sketch above illustrates our response; restoring the original half-round niche and providing a half-dome to structurally stabilize the damaged lintel, allowing the safe distribution of gravitational forces towards the reinforced brick masonry base.

The sketch above illustrates our response; restoring the original half-round niche and providing a half-dome to structurally stabilize the damaged lintel, allowing the safe distribution of gravitational forces towards the reinforced brick masonry base.

* We decided just to include our sketches, photos of the process and images of the finished product. But in Puerto Rico, for far too long, traditional means and methods of construction like brick, stone or rubble masonry, had been lost. During the mid-20th Century, disguised as a way to withstand hurricanes, traditional construction including wood had been replaced by reinforced concrete (and eventually steel) construction.

* We decided just to include our sketches, photos of the process and images of the finished product. But in Puerto Rico, for far too long, traditional means and methods of construction like brick, stone or rubble masonry, had been lost. During the mid-20th Century, disguised as a way to withstand hurricanes, traditional construction including wood had been replaced by reinforced concrete (and eventually steel) construction.