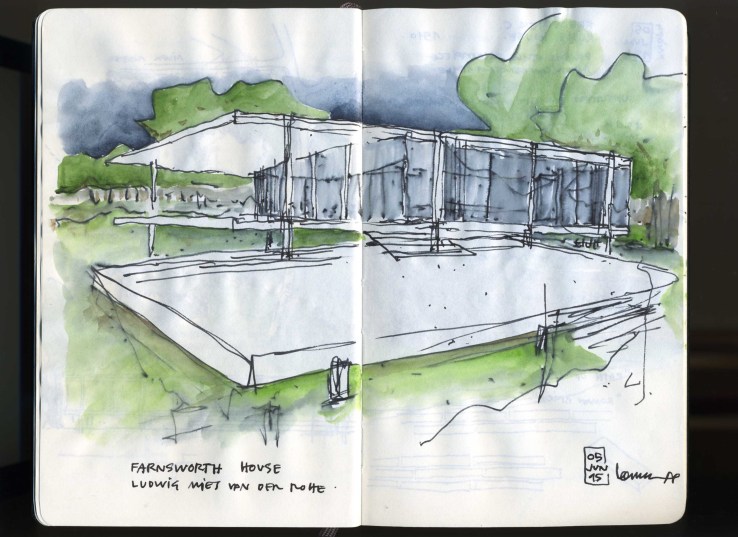

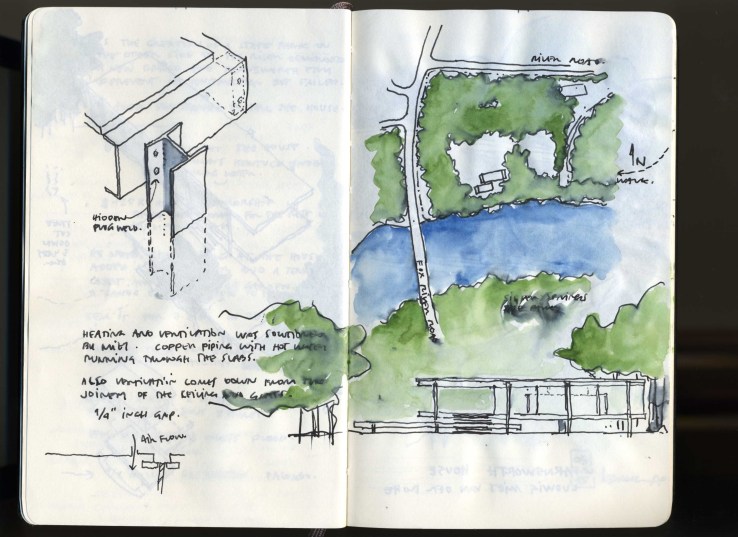

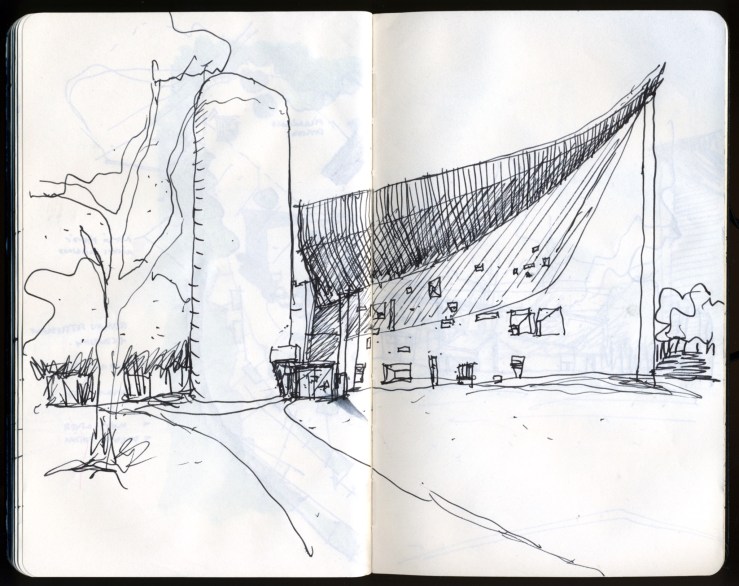

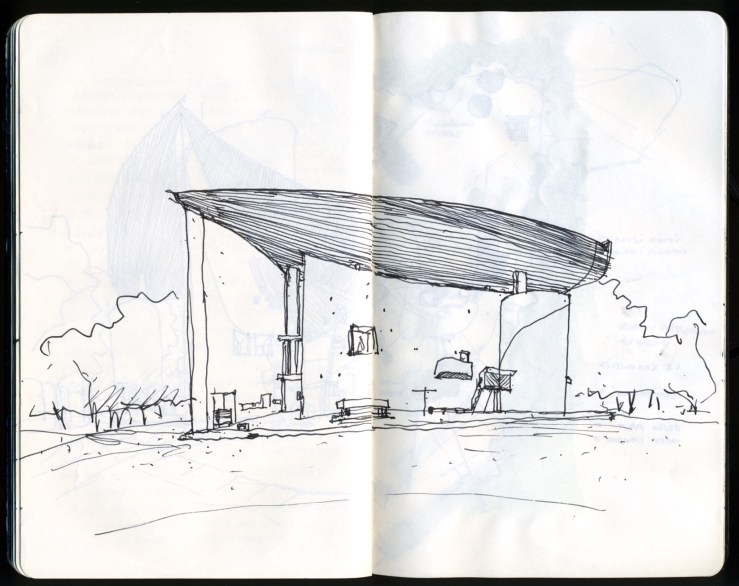

The National Trust for Historic Preservation is considering relocating Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House out of the Fox River floodplain. The idea is to move the structure from its original location parallel to the waterway to a nearby site, still along the river, but on a higher elevation. Throughout the years the house has been affected significantly by floodwaters at least three times. The last major damage occur in 1996 and the restoration costs elevated to almost half a million dollars. At that time, the flood broke windows, damaged the travertine marble floors and ruined the teak cabinetry.

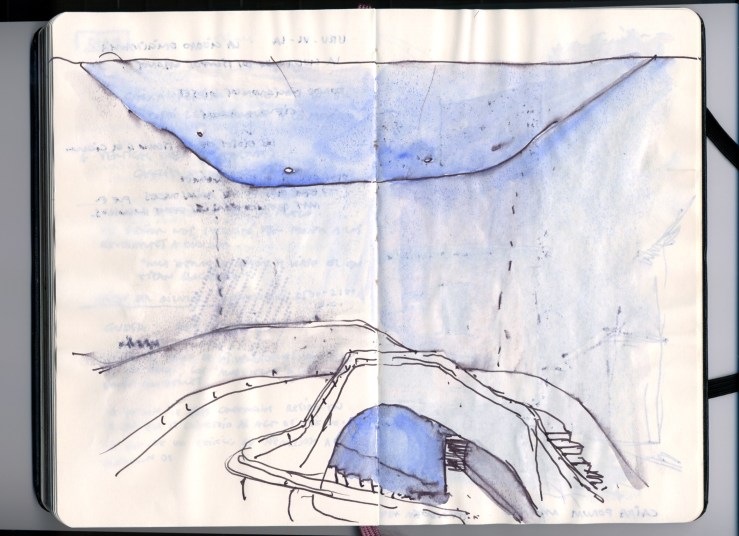

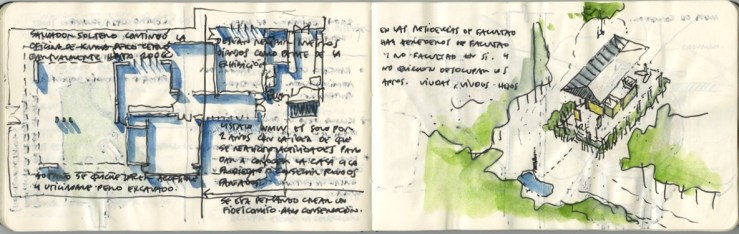

The solution of moving the house is not the only one the Trust has juggled in order to protect the house from further damages. Two additional solutions not requiring to relocate the house have been contemplated so far. One — less viable, although favored by Dirk Lohan, a Chicago based architect and Mies’ grandson — requires the installation of hydraulic jacks underneath the foundations to lift the house during floods. A second one, provides to permanently raise the house on top of a 9-foot mound.

Each one of the alternatives entail major impact on the National Historic Landmark and needless to say, has raised many eyebrows not only on preservationists, but also throughout the architectural community. One of the leading voices is Mr. Lohan who was in charge of the 1996 restoration. He argues that moving the structure “…is not in keeping with the design concept of the house, which was a house in a flood plain, close to the river…The river was part of its immediate environment. To move it to higher ground where it never floods would be ridiculous. You would ask: ‘Why is it on stilts?’ It makes no sense to me.”

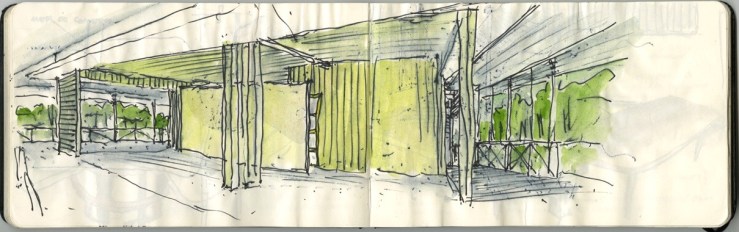

Having visited the house for the first time last month I really don’t see the problem with moving it. Arguably, given the nature of the house, an elevated object that relates to the river just by being in proximity to it and not much else, I see no problem in relocating it to a higher site to relieve the enormous preservation pressure and most importantly avoiding escalating restoration costs.

One knows that the success of the strategy depends on the execution and the careful conditioning of the new site to retain the overall experience. Nevertheless, I strongly believe that regardless of its location the house will continue to inspire future generations if the right action is pursuit, sooner rather than later, in order to move it out of harm’s way.